Around Palais des Beaux Arts /

Their gardens have been parcelled out

Creative Walk + Collective Text, June 11, 2025

Catherine Parayre

Seth Weiner

Charley Condill

Abigail Gorline

Analiese Smith

Emerson Wallace

Mikaila Zanghi

^I. Wittgenstein Haus

Straight lines that look like bamboo, an unlivable house, not truly a house. It’s summer but not sunny. Stark white modern architecture stands out amongst spongy yellow and textured oranges. It stands before us, chunky. A walled villa whose impassible windows reach out to the sky – sixteen of them, not all visible, attached to the ground, to this uninhabitable ground, to wondrous pink and yellow flowers that barely make it out of the soil.

Peaking lots – we step closer to see over the seemingly forever barricades. The slab of a white wall. Trees taller than the house. It feels odd to observe a place with so much overlooked history. We want to go inside and see or touch. Would we see or feel what the family saw and felt? What the Nazi and Russian soldiers saw and felt? Did they want to be here?

Wooden slats hang over the windows. On one of them the blind is starting to drop but gives up before it really begins. It looks like a droopy eyelid. A shy witness to the barracks that left over half a century ago. We think about the geometry of hiding.

This is a place that was not meant to be alive. Windows look in on people annoyed with the home. After the war, it was saved from demolition. It is now an embassy. The walls are paper white, paper flat, and paper plain. The windows are marred by vertical wooden bars, maybe to mimic separate panes, or maybe to keep trapped imaginary enemies. How depressing it must be to look so garishly modern, so structured. Or is it too complicated, not abstract, not colorful, yet beautiful in its own way?

Spiderweb doors, a gate.

Looks like Frank Lloyd Wright was trying to catch flies.

Big white box, prison-like.

Looking like those hamster cages pet stores like to sell.

There’s no good way to see it.

Green tree curtains, white walls. Angular edges reaching up towards the clouds, a bleak beacon hidden behind walls, the full canopy of a tree.

A planting of succulents on the side of the wall, a glade oasis in the modern sea.

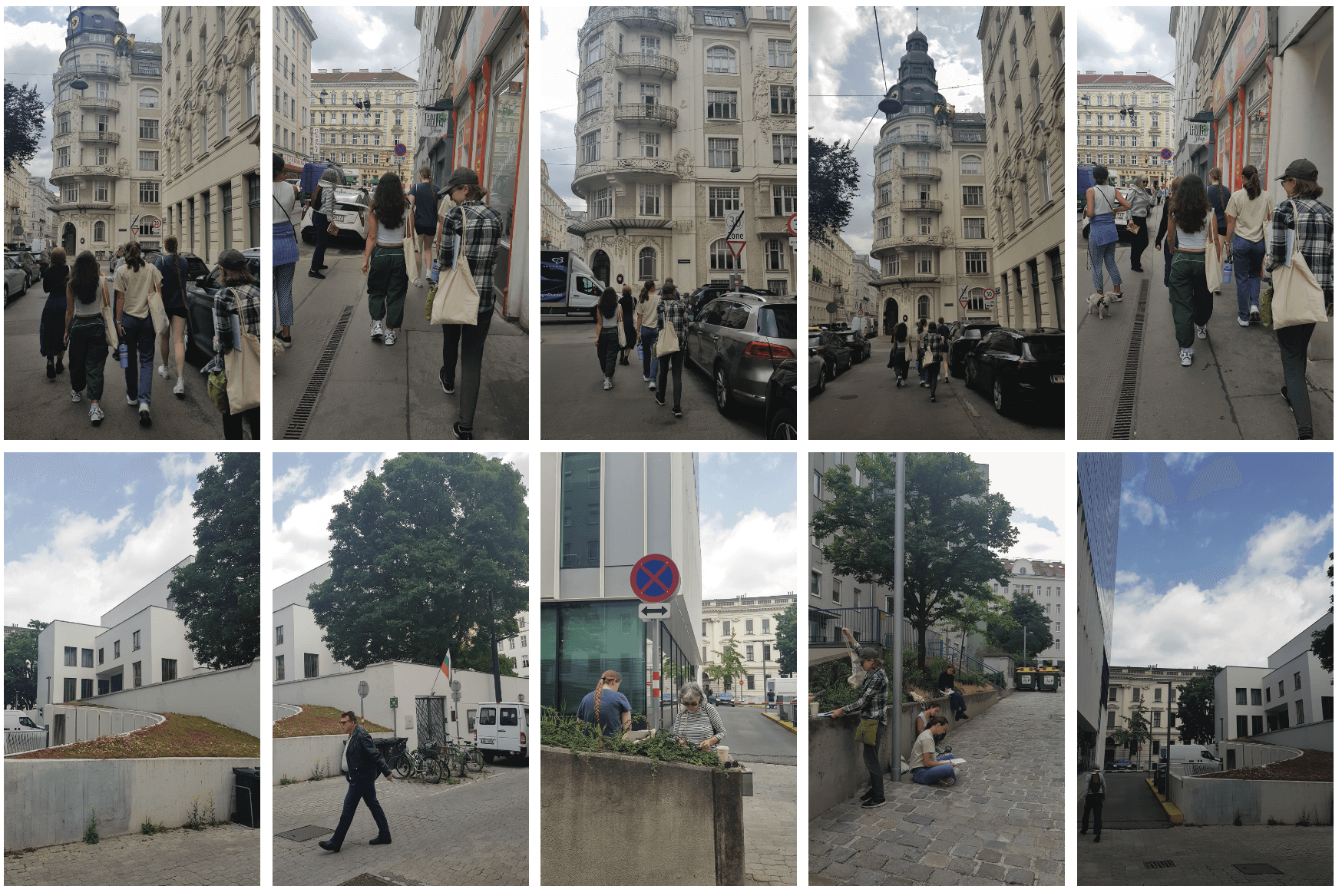

As we walk through the surrounding streets, we notice layers of time and different ways of thinking. Weeds grow through cracks in the stone.

Pedestrians stroll by, unknowing. A woman speaks loudly on the phone, as she walks past an empty terrace overlooking diffident pink and yellow flowers. We hear the motor of a car on standby distilling dark grey clouds over the city, murmuring that we are not welcome. The sewer gurgles in step with an idling car, washes out the mouth of the city underground. On the street parallel to the house a muscular fin de siècle building is squinting. Its eyes are mostly closed.

^II. Palais Rasumofsky

The tops of the pillars that cradle the palace walls are strung up in black nets. Is this an attempt to keep the birds off? We cannot come up with any other reason to cover the most remarkable part of the grand palace.

They have put up the black flag for the three-day state mourning over the entrance – a sheet falling down upon us as in hundreds of other buildings across the city. The old tree at the corner of the street is the only memory of what was once green, of vast expanses. A man shouts; in our backs, bright yellow asphodels.

Today a film crew put blackout curtains over the main entrance. A small crane lifts a car from a parking spot. The straps sing as it hovers into the air and onto the bed of a truck. A production assistant walks by with a large empty water jug to a row of trailers that have banners for self-optimization. A group of kids cross the street and their teacher stands in the middle of the road to keep them safe. Maybe it’s a period piece.

The palace burned down the night it opened. Tsar Alexander must have been disappointed.

Inside, the art turned to ash in a matter of minutes.

Makes us realize we are too attached to our artwork – too materialistic.

We wonder if the walls still remember the flames.

What kinds of things burn? Wood, paper, dried out things.

How do fires start?

Unattended candles,

Fireplace accidents,

Cooking mishaps,

Electrical disasters

Well-placed lightning strikes,

What makes fires worse?

Lots of fuel. Oils, grease.

A car is lifted onto a truck.

The side of the truck says ‘SORRY’.

An ad for ‘Ballerina’ passes by on the back of a bus.

We are sorry the art burnt down.

Yellow flowers smell mostly good.

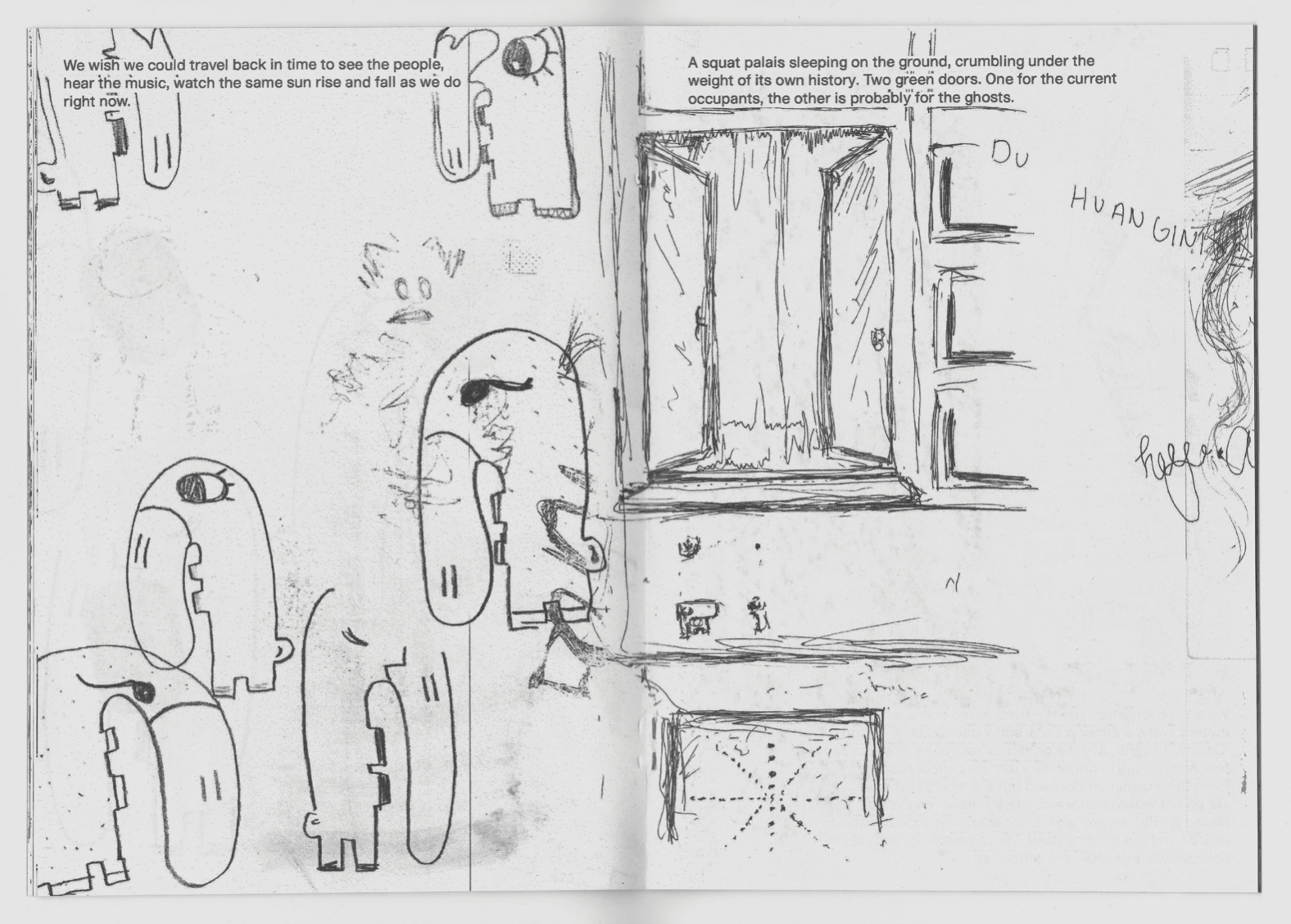

Pink buildings. Yellow buildings. Why are some colorful and others not? What started the fire? Fractured from its former glory, the palace blends in delicate yellows and now greyed whites. Sitting atop are chimney stacks, almost a homage to a loss swallowed by time. We wish we could travel back in time to see the people, hear the music, watch the same sun rise and fall as we do right now.

^III. Palais Salm

A squat palais sleeping on the ground, crumbling under the weight of its own history. Two green doors. One for the current occupants, the other is probably for the ghosts.

We sit in a forgotten street – here, faded ochre, and a few meters away, another palace, softly painted blue. ‘Rome’, ‘Coach’, ‘Laughs’, say the graffiti in front of us. A smiley face too. Another tag in bright blue that we cannot read. Everything within arm’s reach but the words that built it. We do not laugh and look at a heart drawn on the wall. Messy graffiti, sloppy tags. Most adorn the doors or wooden boards, not the building itself. Those painted directly on the palace’s walls are few, are ostracized.

A palace rotting away. The paint is falling off. The end of a palace. But not quite.

Its foundation crumbles, withers away, exposes skeletal innards of wood and brick. It peels itself up off the pavement, pressing away from its settlement – the exposed bricks show the bloody insides of the foundation, as well as puncture wounds whose skin plaster and haphazard stitches have been cut away. Thin boards have been slapped across the decay, but even those have begun rotting. The plywood has something sculptural about it, inlaid and meandering between smooth plaster and two world wars. At one time, this building was a hospice.

The creamy yellow stone of the upper level is cracked and chipping, and the window glass is many layers deep in dirt. Such neglect.

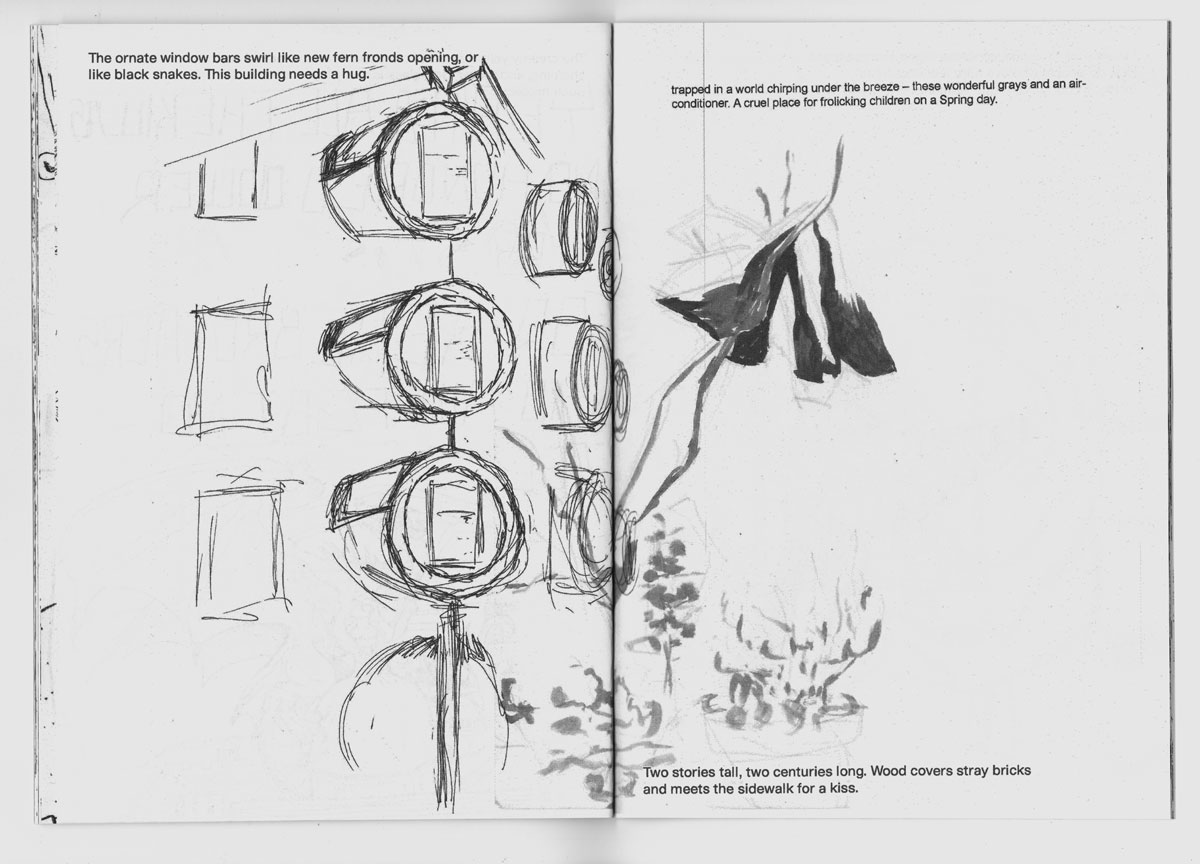

The ornate window bars swirl like new fern fronds opening, or like black snakes. This building needs a hug.

Two stories tall, two centuries long. Wood covers stray bricks and meets the sidewalk for a kiss.

Layers – paint, stone, concrete, wood and red brick.

How do people who live here feel about this?

Inside, a courtyard, a kind woman.

Light yellow, yellow ochre, copper green, and green copper.

We love the word ‘saltpeter’ and wrought iron over the windows. They tell us about rust and water, about many rain showers over the centuries, the varnish of time, the ruined foundations of built places, their endurance and why they’ll fall apart.

^IV. Czapkapark

An elongated park built over the layers of a city sectioned into lots and streets. Walled in and talked in. Green ivy climbing the buildings: a blanketed mass – one organism. Yellow flowers, purple flowers, of all varieties. Wind bugs, flooding from plant to plant.

After winding through a water feature, we land on a mound. Park benches flank the sides; one row is almost hidden in the bushes. A Gemeindebau – municipal ochre, flat, seven stories into the sky – meets a nearly palatial building. They’re stitched together, inseparable from the outside but probably segregated on the inside.

We wonder if the roots of old and young trees connect below the dirt. A critique of how the buildings only meet on the surface. Their trunks and leaves keep a safe distance apart but talk and tangle out of sight.

It is a park for children and adult supervision, maybe more enriching for children than the parks in America. There are graffiti, high hills, and different kinds of play. Even if it might not be the safest park, we feel it is good for the children to learn and play here. Would the children in Vienna be bored with American parks? Most children’s parks there consist of decrepit playgrounds and unkempt grass. It seems as though only wealthy children in America get to be enriched.

A man pushes his little girl in a stroller. There is a tune being played, a timeless lullaby from a father to his child. It’s almost Father’s Day. We miss our fathers.

The man wears air pods to keep from sleeping.

Tree shadows speckle the ground and the sun peeks through for those seeking its warmth.

The benches we sit on show evidence of those who sat here before: cigarette butts at different ages and levels of smushedness, a pull tab from some canned drink, and doodles on the wood. We eat mints.

We hear birdsong, the breeze, cars, and children playing. The man plays a lullaby for his child.

Sounds of construction in the distance.

Purple flowers are speckled with bees.

We remain away from people, so their sounds merge together.

Our nifty bird app hears a Eurasian Blackcap.

He or she whistles, bright, light, singsong beeps. It’s a joyful noise.

The wind runs through the trees and brushes before it reaches our faces, carrying with it the smell of fresh life. Children run about, but they don’t quite scream as playing children might. We hear more cooing and content giggling and the sound of a lullaby a father plays as he strolls around, trying to coax sleep into his child. The bustle of the city is muted by the cradle of the surrounding buildings, giving songbirds their chance to shine. The city has been built up and the city has been torn down, leaving layers and elevations of a shifting landscape. The rear side of the rundown Salm Palace is visible and blends softly into the background.

This elevated park: a way up ending against the vines of a wall protecting the neighbour’s garden. We are quiet; a frightening lullaby drifts out close to us. We see the children play – their future under the trees, under the net of the basketball hoop, trapped in a world chirping under the breeze – these wonderful grays and an air-conditioner. A cruel place for frolicking children on a spring day.

^IV. Czapkapark

An elongated park built over the layers of a city sectioned into lots and streets. Walled in and talked in. Green ivy climbing the buildings: a blanketed mass – one organism. Yellow flowers, purple flowers, of all varieties. Wind bugs, flooding from plant to plant.

After winding through a water feature, we land on a mound. Park benches flank the sides; one row is almost hidden in the bushes. A Gemeindebau – municipal ochre, flat, seven stories into the sky – meets a nearly palatial building. They’re stitched together, inseparable from the outside but probably segregated on the inside.

We wonder if the roots of old and young trees connect below the dirt. A critique of how the buildings only meet on the surface. Their trunks and leaves keep a safe distance apart but talk and tangle out of sight.

It is a park for children and adult supervision, maybe more enriching for children than the parks in America. There are graffiti, high hills, and different kinds of play. Even if it might not be the safest park, we feel it is good for the children to learn and play here. Would the children in Vienna be bored with American parks? Most children’s parks there consist of decrepit playgrounds and unkempt grass. It seems as though only wealthy children in America get to be enriched.

A man pushes his little girl in a stroller. There is a tune being played, a timeless lullaby from a father to his child. It’s almost Father’s Day. We miss our fathers.

The man wears air pods to keep from sleeping.

Tree shadows speckle the ground and the sun peeks through for those seeking its warmth.

The benches we sit on show evidence of those who sat here before: cigarette butts at different ages and levels of smushedness, a pull tab from some canned drink, and doodles on the wood. We eat mints.

We hear birdsong, the breeze, cars, and children playing. The man plays a lullaby for his child.

Sounds of construction in the distance.

Purple flowers are speckled with bees.

We remain away from people, so their sounds merge together.

Our nifty bird app hears a Eurasian Blackcap.

He or she whistles, bright, light, singsong beeps. It’s a joyful noise.

The wind runs through the trees and brushes before it reaches our faces, carrying with it the smell of fresh life. Children run about, but they don’t quite scream as playing children might. We hear more cooing and content giggling and the sound of a lullaby a father plays as he strolls around, trying to coax sleep into his child. The bustle of the city is muted by the cradle of the surrounding buildings, giving songbirds their chance to shine. The city has been built up and the city has been torn down, leaving layers and elevations of a shifting landscape. The rear side of the rundown Salm Palace is visible and blends softly into the background.

This elevated park: a way up ending against the vines of a wall protecting the neighbour’s garden. We are quiet; a frightening lullaby drifts out close to us. We see the children play – their future under the trees, under the net of the basketball hoop, trapped in a world chirping under the breeze – these wonderful grays and an air-conditioner. A cruel place for frolicking children on a spring day.